Using Risk Taxonomies to Speed Up Development and Avoid Churn

We've all been there: the project is nearly complete, there's a deadline, and someone comes to a status meeting with a problem. A big problem. Something that puts the whole project at risk and means we have to delay, and maybe even rethink our approach.

And we'll ask: why didn't we see this earlier? What could we have done differently to discover this issue before we'd done so much work?

Enter: Risk Taxonomies.

Marty Cagan talked about Risk Taxonomies in his book INSPIRED and suggested the following types of risk for product development, and who might be responsible for addressing each type:

- Business Viability Risk (product manager): can we provide this in a way that makes sense for the business, with good unit economics, etc?

- Value Risk (product manager): is this actually valuable to our customers, do we have evidence that this addresses an underserved outcome?

- Usability Risk (designer): can we make this usable for customers, without requiring a steep learning curve, have we reduced enough complexity "above the line" of customer abstraction?

- Feasibility Risk (engineer): can we actually build this, in a reasonable amount of time, with a reasonable amount of resources?

These are high-level categories for a cross-functional team to address. Between the "product/engineering/design" trifecta, we can cover the whole range.

As engineers on these teams, we'll need to focus on feasibility: can we actually do it? (This is a great question for an engineering manager to delegate, by the way, with appropriate coaching and support.)

To answer that effectively, we need to focus on the biggest risks to the project first, the ones that, if we cannot address them, we may not be able to finish the project at all. To find those existential risks, we can ask a series of questions for each thing we need to be able to do:

- Is this a problem that has never been solved before?

- Is this a problem that is on the bleeding edge of some technology or technique?

- Is this a problem that has been solved, but never in our organization or tech stack?

- Is this a problem that we have known solutions for, and can we use those?

- Are there routine tasks that are well within the capabilities of our systems, things we as team do regularly?

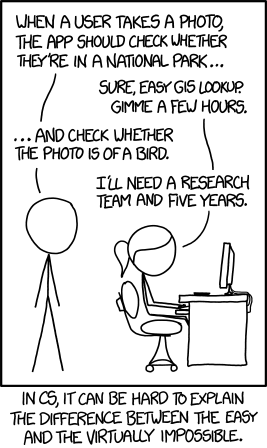

For an example of problems that have never been solved, we can look at the xkcd comic Tasks. In 2014, when Randall Munroe published this comic image categorization had not yet been solved in a useful, reliable way. If a product or feature depended on the ability for computers to recognize objects in an arbitrary image, it was likely that product was, in 2014, impossible to build with reasonable resources and on a reasonable time frame. This means the project needs rethinking—or that this needs to be the very first risk you tackle via proofs-of-concepts and other research. (And, to Randall's credit, five years later, around 2019, it was possible.)

An example of a bleeding-edge problem: five years or so ago, a team I was on wanted to automate getting structured data out of complex policy documents, a task that is slow and error prone for humans. There were a couple of brand new start-ups and cloud services that were promising this via OCR and machine learning, but none of them had high success rates, or could get us data in a sufficiently structured way. (Now, at the end of 2025, this is much more reliable.) At the time, the first thing we had to do was test whether any of these bleeding-edge products worked well enough for our needs. We determined none of them were—at the time—reliable enough that we could actually take the human time out of the process. We had to look elsewhere to help our operations teams save time and improve quality.

As we go through the things we need to do, we can categorize them with these questions. Requirements in the first few groups are where research tasks, or "spikes," like building proofs of concepts, or even looking into published CS research can deliver significant derisking value. The goal of this research is not to decide if something is possible, it's to determine how long it might take and how uncertain it is. Can we do this in a couple of hours, sprints, or do we need a research team?

Encountering these problems does not necessarily mean the project is impossible: it means we'll need to ask more questions. Is there another way we can get the same, or a similar outcome? Is this capability actually critical to providing user value, or can we still ship something valuable without it? If it's a problem that has been solved, but never by us, is there a vendor we can use, at least in the short term?

When a problem is risky, we don't need to say "no," we can say "this is what it would take."